Look this way big fella! It’s like herding cats…

I tend to think of wildlife portraits as finding the essence of an animal. Just like human portraits, taking animal portraits follows a lot of the same rules with a few major differences. Whilst you’ll have the advantage of not having to worry about hair styling, wardrobe and makeup, you’ll spend a lot of time waiting for just the right moment to actually take a shot. Never work with animals or children they say. And they’d be right: children can be extremely unpredictable and uncooperative. Not all the time of course. But animals – in particular wildlife – well that’s even worse: you have very little chance to direct the shot. And they might not even turn up. If that lion doesn’t look at you, you can’t take a full face portrait with him looking right at you. Luckily, some animals are curious to see what has just stopped in front of them, like giraffes for example. But be quick. If you’re in a safari vehicle, you should have your camera ready for the shot before you stop. The animals are most interested in you at the point you arrive. After that (if they haven’t scarpered) they’ll often lose interest and never look at you again. Often though, animals keep a constant look-out and will turn to look in different directions repeatedly on the lookout. Even predators do this, so their kills don’t get stolen. Try to catch the animal looking directly at you if possible.

Giraffes are curious creatures and will often stand and stare, as long as you don’t spook them

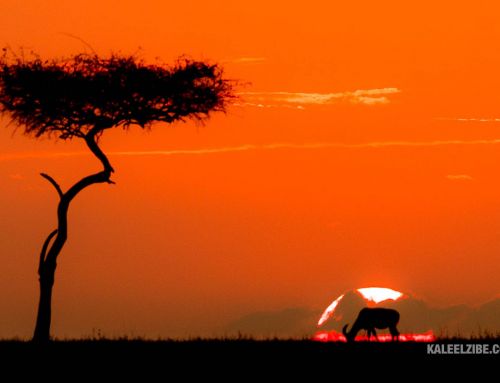

Luck plays a big part. But as with anything else, it’s possible to ‘refine’ luck by shortening the odds. Do your homework and find out when the animals are likely to be around. Go with a guide, or someone who knows the animals to increase your chances. There are times when certain animals don’t do much: lions are a great example! If you turn up at midday, they’ll be asleep. Find them at dawn or dusk and you’ll see them utterly transformed.

When is the best light? Usually golden hour is best, not just because it’s a lovely colour, but also because the light comes in at more of an angle and creates a more 3D effect. Or it might create back-light for extra drama. All is not lost if the light isn’t great though: often, converting to black and white and carefully processing the image can make a great image.

Gorillas are fantastic subjects for portraits. They’re playful, intelligent, wistful and most of the other things that humans are. They also work very well in black and white

Ok, so let’s talk technical stuff. In order to create a powerful connection with the animal, and so that you can show something of its character, you’ll have to decide how close to get. Most portraits work best when the animal is dominant in the frame. This is also a time when the rule of thirds doesn’t so much need to be used for the placement of the whole animal, as certain strong features of that animal. Think eyes on a thirds, or a hand on crossing thirds for example. Consider this portrait of a cheetah. Two of the signature features of cheetahs are the black ‘tear’ lines down each side of the nose, and those wonderful eyes. If you photograph the cheetah so that it’s small in the scene, those features won’t have much impact. So, zoom in with a long lens and make sure the eyes in particular are sharp. You’ll notice with the gorilla above that just one sharp eye works really well too. Zero sharp eyes doesn’t work, however! Speaking of sharpness, use as fast a shutter speed as you can get away with. If there’s not much light, crank up the ISO and use a beanbag or tripod. I know visual noise is undesirable, but sometimes a little noise is acceptable and is easily removable afterwards.

Close-up of a cheetah’s face: orange eyes and black tears. You can also see that it has just made a kill

Separating the animal from the background is a good way to make it stand out. Try to use a shallow depth of field: as wide as you can go with the aperture. Be aware that any long noses may be out of focus if you’re at a really wide aperture, even if the eyes are in focus. In the world of lenses, I’m afraid long, fast lenses really do make a difference – and cost a whole pile of cash. Not only will you get closer in, but the quality of the shot will be better: sharpness, background blur (bokeh), contrast and lack of aberrations. It’s often the lens that’s more important than the camera. My sweetest lens was a Nikon 300mm f/2.8 and it cost an arm and a leg. I still haven’t replaced it since moving to Sony, but the intention is there.

This post isn’t all about African mammals (although when in Africa, they are significantly easier to spot than UK wildlife!) I like to call this photo ‘Windy Day”. Red squirrels have delightful ear tufts in the winter. The tufts are part of what makes a red squirrel a red squirrel

As for post-processing, I like to do quite a bit to make sure the image really pops from the screen. As well as the usual exposure, white balance and so on, I usually add a bit more contrast, draw down the blacks and push up the whites and sharpen a bit more than I’d normally do. Also a touch of clarity and maybe a vignette or radial exposure filter with some dodging and burning. I realise that if you don’t know what these terms mean, this all may be a bit much to hear. It’s just to explain that my style is to perform quite a few tweaks to the image afterwards. Not always, but usually. And not always lots: usually subtlety is the best.

In this buffalo image, I’ve really gone to town with quite a bit of post processing. I felt it warranted the adjustments.

Whereas with this young chacma baboon in Botswana, I didn’t really want to do much, other than lift the shadows to balance the foreground lighting a bit

It’s worth pulling back a little sometimes and not cropping in too much. Whereas the cheetah’s face warranted a long lens and some cropping in post, the baboon above looked like it needed to a bit more space. It’s a portrait in its environment. The photo is still simple enough and the animal is the main subject, but there’s a little of its environment included, which I think enhanced the portrait.

Leave A Comment